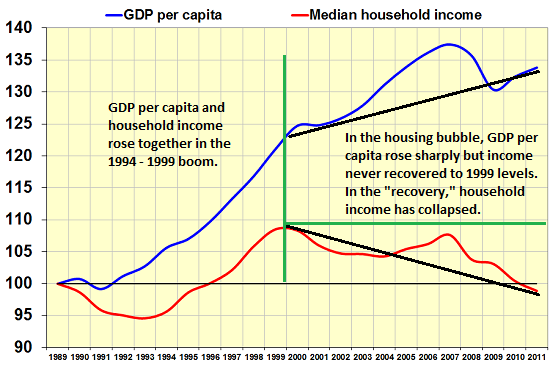

Mervyn King’s decade at the Bank of England was a disaster. The Bank was too slack during the long and indisciplined boom, under prepared for the crash and playing catch-up thereafter. The legacy of Lord King’s (and Gordon Brown’s) career has been an economy still limping along far below peak output, real wages caught in a vice. Few recent careers have more comprehensively failed.

Lord King at Wimbledon

But it wasn’t all bad. In that long decade of failing banks, easy money and over-protection of creditors, Lord King at least clung to one last shred of decency. If a failing bank, or other lender in distress, wanted to borrow money from the Bank of England, it would be obliged to offer reasonable collateral, borrow for relatively short periods – and be made to pay real money for the privilege. Yes, the result could look punitive, but that, in Lord King’s mind, was the point. Banks are meant to run themselves so that they do not need to obtain bailout funds from the Bank of England. If they foul up, then they – their shareholders, managers and creditors – should be on the hook, not taxpayers or prudent savers. It’s a rule that has served capitalism well enough for the last five centuries. Lord King was the last major central banker on Earth to cling to this belief. He was alone, but he was right.

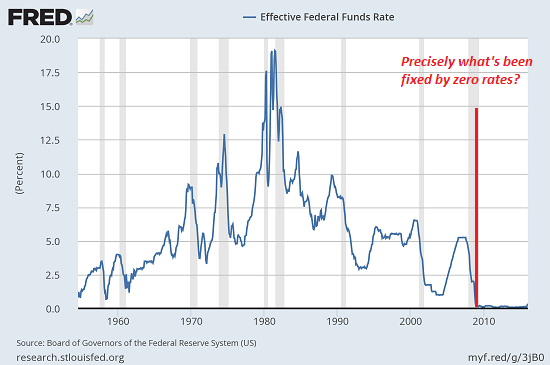

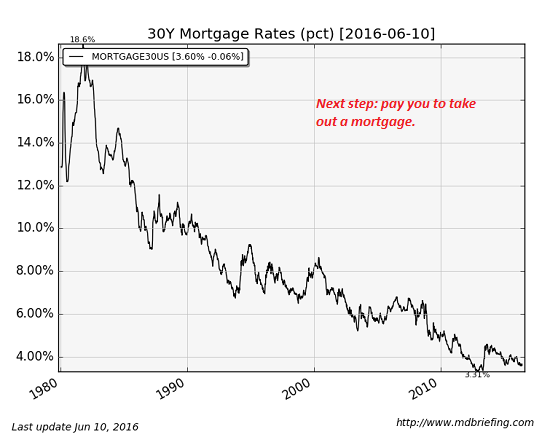

Mark Carney has ditched all that. In a recent speech, the new Bank Governor spoke about the need to “keep up” with developments elsewhere and promised to make emergency credit cheaper and quicker, adding that the range of assets the Bank would accept as collateral would be wider. In effect, this is a promise of cheap money, slackly administered – a fire hose of liquidity.

The head of the European Central Bank (and, like Mr Carney, once of Goldman Sachs), Mario Draghi, once promised to save the euro by “doing whatever it takes”. That promise has led to some sweet returns for the financial sector, but at the cost of keeping rotten banks afloat with loans and encouraging the good ones to weaken their balance sheets. Thanks to Mr Carney, we’re now getting the same.

Canada’s housing bubble is ready to pop, UK next!

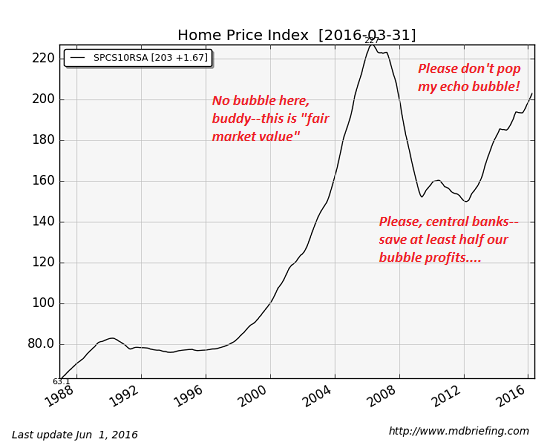

The move is disastrous. The Bank is already permitting yet another unsustainable boom to run unchecked. Rightmove, the property website, last week said London house prices had risen £50,000 in a month. The Bank liquidity pump is supplying petrol to that fire, while George Osborne’s Help to Buy scheme strikes the match.

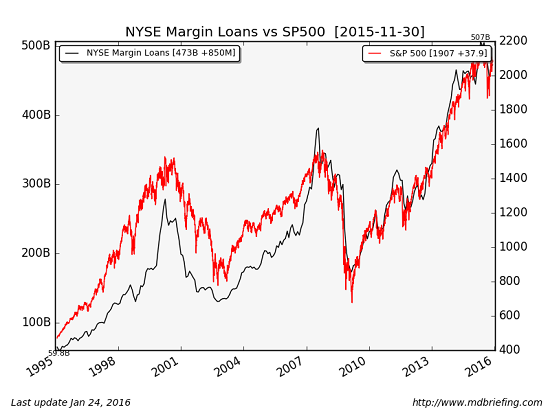

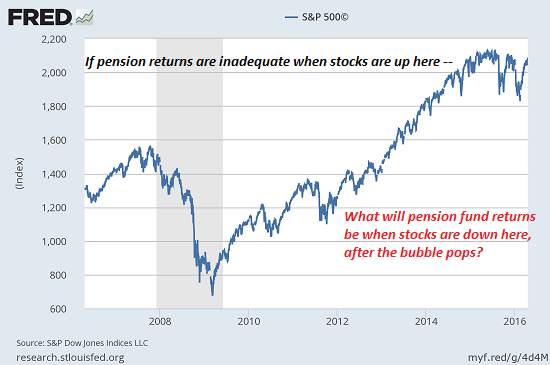

Less widely noted, but equally crucial, the UK equity market has almost doubled since its 2009 low, while the German and many US equity indices hit all-time highs. The tech-heavy Nasdaq exchange is now seeing the return of dot.com-bubble valuations, while junk bonds trade at interest rates well below those offered by AAA-rated bonds some 20 years back. Indeed, the US Federal Reserve, normally so relaxed about these things, became so concerned last week that it sent a warning letter to the likes of Goldman regarding the “low quality of leveraged loans”.

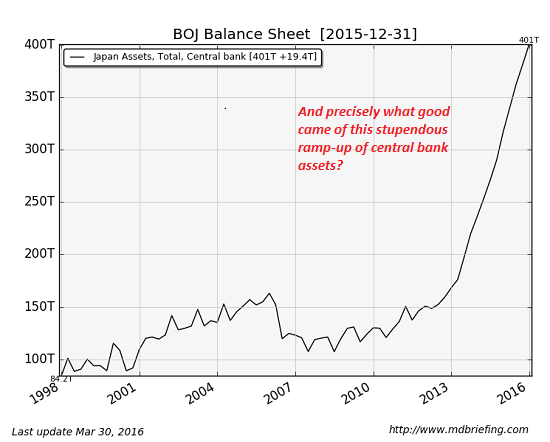

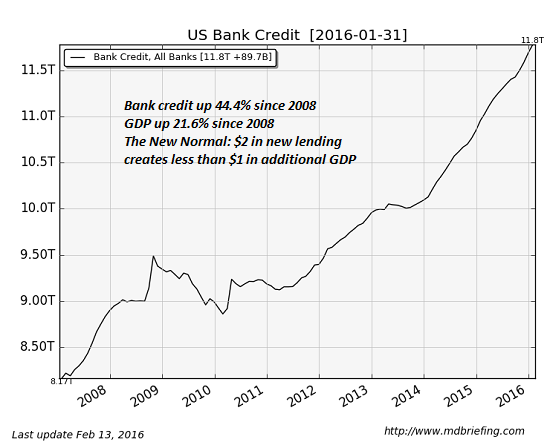

Given the state of the global economy, the only possible cause of these surging asset prices is the wholesale purchase of financial assets by the Bank, the Federal Reserve and other central banks. This is central banking via asset bubble creation: QE Infinity, a path without exit.

Mr Carney, far from wanting to damp this activity down, seems keen to extend and enlarge it. The assets (and also the liabilities) of the British banking sector are now around four times national income. You only have to look at the destruction wreaked on Ireland and Iceland to understand the risks of running an engine on a chassis too small to bear the load.

But Mr Carney doesn’t care. Noting nonchalantly that, based on current trends, British bank assets would grow to nine times the size of the economy by 2050, he suggested – quoting the former Barclays chief Bob Diamond – that it was time to welcome an industry that can “be both a global good and a national asset”.

You do have to wonder if his departure from the land of hockey pucks, grizzlies and maple syrup has sent the poor man crazy. Yes, of course, the UK cannot simply wish its financial industry away from these shores. And yes, it creates jobs and pays taxes. And yes, the Bank of England is making some genuine efforts to improve both bank capitalisation and bank risk management.

But who is he kidding? No country ever, anywhere, has managed to abolish financial crises. Since the birth of modern banking, there have been regular crises. No sooner is one stable door locked, bolted, watched and guarded, than a new door emerges somewhere in the unlit spaces far from view – somewhere you haven’t even thought to look. Our current financial crisis has already caused the longest depression not only in British but in European history. It’s almost impossible to imagine how bad the next one will be.

The fact, as psychologists have observed, is that humans are prey to both optimism bias – things will turn out better than they do… it’s different this time… hey, I’m smarter now – and anchoring bias – the future probably looks a little like today.

To these two factors add the reality that the “sell side” in financial markets – roughly speaking, Goldman Sachs and its peers – is far better resourced, vocal and politically connected than the poor old “buy side” (roughly speaking: you and your battered old pension fund). The result is that our financial markets are at permanent risk of inflated valuations and irrational exuberance.

We can’t change reality. Greed will always have a tendency to win out over experience. Asset markets will always want to froth. Industries with money will always secure more political influence than they ought to have. The best-regulated markets will always be well protected against the last crisis, but vulnerable to the next one.

These things we can’t alter. They are the financial world’s equivalent of Original Sin – the result of our fallen state. But we don’t have to make things worse. We could tackle excess leverage and poor asset quality instead of just playing “extend and pretend, pray and delay, divert and deflect”. We don’t have to tell bankers that moral hazard no longer applies. We don’t have to use central bank (that is, in effect, taxpayer) money to inflate unsustainable asset bubbles. We don’t have to watch complacently as yet another unsustainable boom is born of yet another unsustainable bubble.

A crisis is unfolding, born of excess debt and excess leverage in toxic combination. That crisis is unfolding now. And neither Mr Carney nor our politicians are doing anything about it.